Digging a deep hole by defying an order

IN 1950 I was in the final phase of my flying training at RAF Heany, near Bulawayo in Southern Rhodesia – now Zimbabwe. Rhodesia was then a forward-looking crown colony with dominion status in the offing.

Before joining the RAF, while learning to fly at a club, I realised that flying, in some form or another, was the only life for me and now I was on the road to becoming a professional pilot. I was even getting a little pay, but the RAF discipline was something I found very difficult to cope with.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAt Heany, it was in fact nearly non-existent compared with training in the UK. You can’t really have heavy discipline when your uniform consists of just a grubby pair of khaki shorts and a shirt.

When I had about three more months to go, Heany was visited by the trappers from the Central Flying School. Trappers were generally disliked throughout the RAF. Their job was to make sure flying standards remained extremely high and techniques remained standardised.

They would pick ordinary pilots from the units they visited and give them a thorough test flight; not popular at all. We were told cadets would have to fly with these people so I dreaded the prospect of being picked to do so.

At about that time, my left thigh was scratched badly by some thorns while I was walking out in the bush. The scratches soon became septic, my leg swelled up and became painful, so I reported sick. The MO grounded me at once, which annoyed me, as I hated the thought of not being able to fly.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI limped back down to the flights and saw my name down to fly with the trappers next day. Oh no, how could I cope with that one?

If I went to the flight commander and told him I had been grounded by the MO, it would look as if I was ‘chicken’ when it came to difficult situations; someone with no guts. My way of thinking in those days could never allow that to happen, but I’ve grown more sensible with age. I did my flight with the trapper.

For some reason that trip went very well, though the trapper never said so to me; all he did was grunt – trappers have a typical way of grunting. I was called for by the squadron commander and went into his office shaking in trepidation, apart from being in considerable pain from my leg.

My instructor was with him, which boded ill, but I was amazed. He congratulated me and told me I had helped to show that the unit worked to excellent standards.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs a reward my flight commander sent me off on an hour’s solo. “Don’t bother about exercises, just enjoy yourself, do some aerobatics and beat up clouds.”

It was the hot season when great thunderstorms build up over the veldt, making flying very bumpy. Landing conditions could get nasty with sudden gusty changes of wind direction, which were not always easy to anticipate.

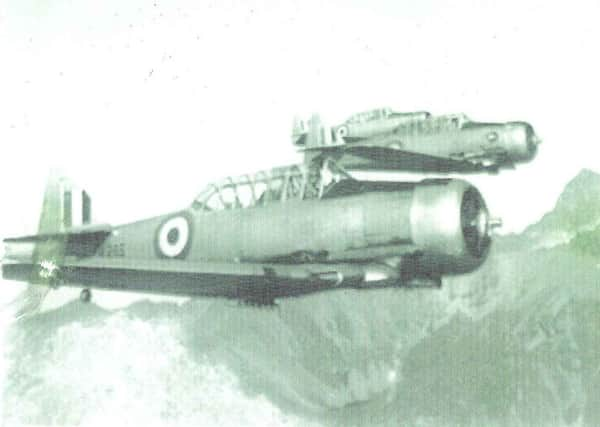

A Harvard was always prone to swing during the landing role if you did not use the rudder correctly. It was all part of flying Harvards, something you dealt with as necessary. If you didn’t, the swing could quickly develop into a ground loop, which would break the aircraft; that being a heinous crime.

So that afternoon, as soon as I noticed a thunderstorm looming up, I came straight back to the airfield. My leg was painful and I would be glad to land. It happened; just as the tail was about to touch the ground, a nasty little crosswind gust caught me. Too late, I had seen the dust devil starting to rise ahead, and it should have been easy to deal with; just a quick bit of rudder work, but my grounded leg did not react and co-operate as it should have done.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI did not stop the swing as was necessary. The tail came round and we came to an abrupt halt, pointing back to where we had come from. The left wing was stuck up at an odd angle and the right wing angled down towards the ground. I had ground-looped the aeroplane and bent the undercarriage.

It seemed to taxi satisfactorily, so I headed slowly in and parked. There was a reception committee consisting of, among others, my flight commander and my instructor; plus the usual onlookers. I felt ghastly; this was the end.

I was told to go straight into the squadron commander’s office. He had also witnessed the episode. What could I say? Should I tell this all-powerful man I was grounded and roll up my long, floppy shorts, showing him my swollen thigh, while explaining this was the reason for my terrible lack of flying ability, or should I just see it out?

A medical officer’s word was law, so I would be guilty of directly disobeying an order. That could really mean bad trouble for me. On the other hand, damaging an aircraft would hold the prospect of the ‘Scrub’, ending my RAF career.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdI decided to stick it out. If they did scrub me, I could then admit to having been grounded and would thus be able to leave with a certain amount of honour, I hoped.

The strip that was torn off was long, powerful and never to be forgotten, but my punishment was just to dig the squadron commander’s garden every day during all my time off for the next two weeks. It was not really a garden, just hard, bare, solid Central African earth; not easy digging.