A history of Horsham in plagues and pandemics

Interestingly, it was a pandemic that influenced the naming of some towns and villages in the district.

Towards the end of the Roman Empire, a plague ravaged Europe, killing somewhere between 13 and 26 per cent of the continent’s population.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe Justinianic Plague, named after the Emperor of the time, Justinian I, was transmitted by fleas found on rodents.

Some say the outbreak made Anglo-Saxon conquests of Britain easier, as the number of invasions increased in its aftermath.

When the Saxons arrived in Sussex, it was not a land full of people, but woodland and shrubbery.

The Roman names of many places disappeared. They were renamed after what was found in the natural landscape: Horsham – a place where horses breed, Storrington – a place where storks can be found, Slinfold – a pen for sheep, Cowfold – a place for penning cattle before taking them into the woodland, and Henfield – a high field.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdWhen the infamous Black Death arrived in Britain in 1348, people fled cities for the countryside in the belief that cleaner air would protect them.

Caused by the same bacteria that caused the Justinianic plague, the Black Death pandemic killed an estimated one third to two-thirds of the population of Europe.

It was a debilitating illness that caused fever, fatigue, swellings in the groin and armpit, sores, and frequently resulted in death.

The large number of deaths meant that there was a shortage of workers in key trades.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThis particularly hit the Wealden iron industry in Sussex and surrounding counties.

However, the demand for iron remained high, so wages rose by 150 per cent to combat the shortage of workers.

The price of iron also went up as a result. The records of the Manor of Petworth in 1349/50 wrote: “… and for iron bought for maintaining the ironwork of the ploughs this year 8s 4d, and so much because iron is dear by reason of the mortality.”

The Great Plague of London in 1665 lead to the deaths of around 100,000 in the city - 6,988 in the first week of September.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe plague caused a financial crisis, as the rich left the city as quickly as they could, without concern for the poor.

However, many religious groups stayed to help the sick. Nonconformist ministers, who had been banished from their previous parishes under the 5 Mile Act, returned to tend to those struck by the plague, and preached on the frivolity of the court.

Many Quakers remained in the city, with an estimated 1,177 Quakers dying as a result. They used their connections to rural areas to organise relief aid.

The next large pandemic to hit Horsham was Spanish flu, so named because the Spanish were neutral at the time of its outbreak in 1918 and covered the outbreak in the greatest detail.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt killed millions all over the world – between three and six per cent of the world’s population.

Unlike most flu viruses, the Spanish flu attacked young adults more violently than the old and the very young, and when it did attack people could die in a day.

Professor Roy Grist, a Glasgow physician, described the infection: “It starts with what appears to be an ordinary attack of la grippe [influenza]. When brought to the hospital, [patients] very rapidly develop the most vicious type of pneumonia that has ever been seen.

“Two hours after admission, they have mahogany spots over the cheek bones, and a few hours later you can begin to see the cyanosis [blueness due to lack of oxygen] extending from their ears and spreading all over the face.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“It is only a matter of a few hours then until death comes and it is simply a struggle for air until they suffocate. It is horrible.”

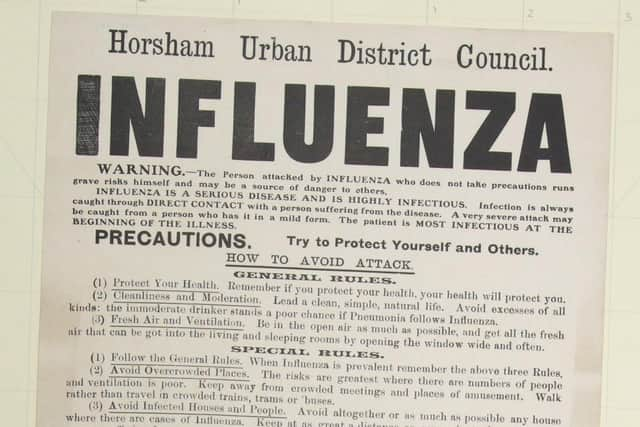

In November, posters were distributed around Horsham.

The message came too late for many people. The Horsham High School log book in 1918 records: “Oct. 22nd Closed school for a longer half term as 25% of girls absent from influenza, + Miss Wagstaff still absent (tending her sick father) Miss Walker Student teacher also absent. Oct. 29 Reopened School. Miss Wagstaff still absent (her father died on Oct. 27) 30 pupils absent through influenza.”

Across the UK, councils were spraying streets with disinfectant, closing meeting halls and shutting theatres.

However, the country still turned out for Armistice celebrations, which led to a national second wave of infection.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOn November 3, 1918, a week before Armistice, the News of the World reported a number of ways to combat the epidemic, including: “Wash inside nose with soap and water each night and morning; force yourself to sneeze night and morning, then breathe deeply.

“Do not wear a muffler; take sharp walks regularly and walk home from work; eat plenty of porridge.”

Despite its great impact, within two years the Spanish flu had been consigned to history books.

A message from the Editor, Gary Shipton:

Thank you for reading this story on our website.

But I also have an urgent plea to make of you.

In order for us to continue to provide high quality local news on this free-to-read site and in print, please purchase a copy of our newspaper as well. With the coronavirus lockdown having a major impact on our town centres and many of our valued advertisers - and consequently the advertising that we receive - we are more reliant than ever on you buying a copy.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdOur journalists are highly trained by the National Council for the Training of Journalists (NCTJ) and our content is independently regulated by IPSO to some of the most rigorous standards anywhere in the world. Our content is universally trusted - as all independent research proves.

As Baroness Barran said in a House of Lords debate this week on the importance of journalists: “Not only are they a trusted source of facts, but they will have a role to play in rallying communities and getting the message across about how we can keep ourselves and our families safe, and protect our NHS. Undoubtedly, they have a critical role.”

But being your eyes and ears comes at a price. So we need your support more than ever to buy our newspapers during this crisis. In return we will continue to forensically cover the local news - not only the impact of the virus but all the positive and uplifting news happening in these dark days.

In addition, please write to your MP urging the Government to provide some additional financial support for local newspapers and their websites like this one and ensuring that supermarkets continue to stock them. I cannot stress enough how important such an intervention would be.

We thank all our readers and advertisers for their understanding and support - and we wish YOU all the best in the coming weeks. Keep safe, and follow the Government advice. Thank you.