Ground-breaking study shows life near Chichester 480,000 years ago

The internationally-significant site has been subject to archaological digs and meticulous study for nearly 50 years and a new study, funded by Historic England and undertaken by archaologists at UCL.

Speaking to this newspaper, the project lead Dr Matthew Pope, said the latest findings show the humans as ‘highly sociable’ and takes a look at the butchering of a horse by the group of 30 to 40 humans.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Mattew Pope said: “In this landscape we have one of the best preserved ice-age landscapes in the entire world with, not only artefacts and bone but it allows us to look at it in miute-by-minute detail.

“Boxgrove has always been celebrated and there have been a number of major works on its archaeology for 20 years.

“It’s an incredibly important site right on our doorstep.”

The findings of the study led by UCL Institute of Archaeology are detailed in a new book ‘The Horse Butchery Site’, published by UCL Archaeology South- East’s ‘Spoilheap Publications’.

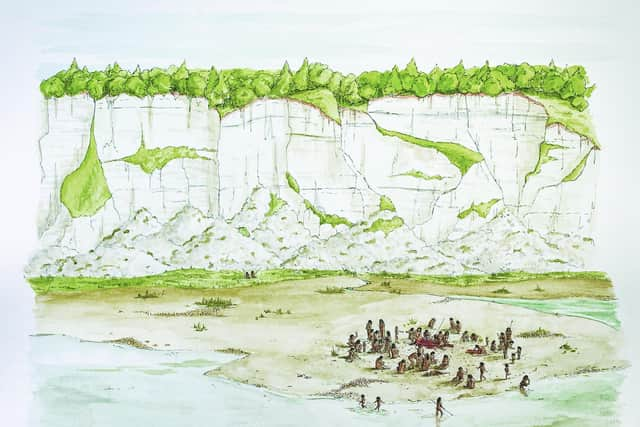

The study pieces together the activities and movements of a group of early humans as they made tools, including the oldest bone tools documented in Europe, and extensively butchered a large horse 480,000 years ago.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDr Pope added: “This was an exceptionally rare opportunity to examine a site pretty much as it had been left behind by an extinct population, after they had gathered to totally process the carcass of a dead horse on the edge of a coastal marshland.

“Incredibly, we’ve been able to get as close as we can to witnessing the minute-by-minute movement and behaviours of a single apparently tight-knit group of early humans: a community of people, young and old, working together in a co-operative and highly social way.”

The Horse Butchery Site is one of many excavated in quarries near Boxgrove an internationally significant area – in the guardianship of English Heritage – that is home to Britain’s oldest human remains.

The site was one of many excavated at Boxgrove in the 1980s and 90s by the UCL Institute of Archaeology under the direction of Mark Roberts.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn the course of excavating the site, more than 2000 razor sharp flint fragments were recovered from eight separate groupings, known as knapping scatters.

These are places where individual early humans knelt to make their tools and left behind a dense concentration of material between their knees.

Embarking on an ambitious jigsaw puzzle to piece together the individual flints, the archaeologists discovered that in every case these early humans were making large flint knives called bifaces, often described as the perfect butcher’s tool.

Questions still remain over where the Boxgrove people lived and slept and even what these people, ascribed to the poorly understood early human species Homo heidelbergensis, looked like.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAnswers to those questions may well rest in the wider 26km ancient landscape, which lies preserved under modern Sussex.

The project was funded by Historic England, the Arts and Humanities Research Council with support from the UCL Institute of Archaeology, the Natural History Museum and the British Museum.