Chichester Festival Theatre - how it all began...

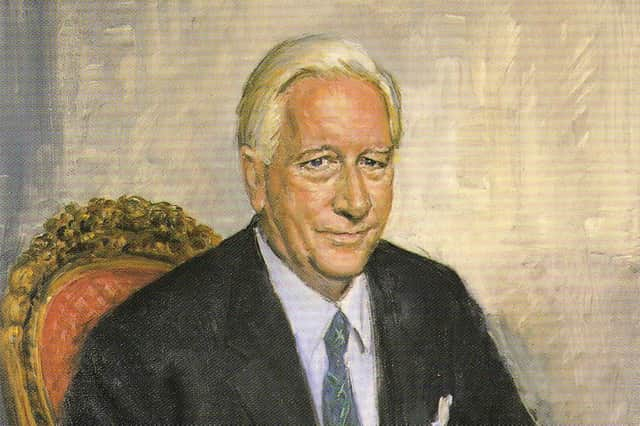

But the vision which coursed through the late Leslie Evershed-Martin was truly remarkable. It was a vision which gave us Chichester Festival Theatre – against all the odds.

It shouldn’t have happened; it really shouldn’t have been manageable; and yet finding the right people and galvanising them every step of the way, Evershed-Martin succeeded somehow in turning vision into reality.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdNot for nothing did he call his story The Impossible Theatre when he wrote an account of theatre’s very earliest days to mark the theatre’s tenth anniversary.

In it, he recalled the day he conceived what was to become Chichester Festival Theatre – a story which has become the stuff of Chichester, and indeed theatrical, legend.

It’s an extraordinary tale of far-reaching ambition amid domestic concerns. It seems that he was simply was sitting at home, the family variously engaged, on the blustery night of January 4 1959.

“I was half-reading, half-viewing as Huw Wheldon appeared on the screen to present his programme Monitor, in which he reviewed the latest achievements in the arts […] The programme’s subject was the story of a theatre in Canada, the Stratford, Ontario, Shakespeare Theatre, told by an interview with Dr (now Sir) Tyrone Guthrie, the renowned theatrical producer […]

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“But what truly enthralled me was the history […] of the community effort behind the realisation of the Stratford venture.”

Stratford was roughly the size of Chichester and yet the community had wrought a miracle – a fact which set Evershed-Martin’s mind racing.

He saw the huge potential of Stratford’s thrust stage, an arrangement which allowed the audience to sit on three sides of the action, rather than simply sitting staring face on at a raised, curtained stage.

Based on the character of Greek and Elizabethan theatres, it was an arrangement that allowed the audience a much closer involvement with the actors than would be the case with a traditional proscenium arch stage – a fact which opened up exciting opportunities.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdEvershed-Martin wrote: “I could see the immense dramatic possibilities of the thrust stage, where the audience were no longer peering into a room at its occupants but were, in effect, in there with them.”

Evershed-Martin saw too the importance of peopling that stage with world-renowned actors. He realised that it needed to be commercially viable (and not “dragged down by heavy debts and placed in need of subsidies from civic and state funds”).

And he wondered whether he could make it happen in Chichester – no small dream at a time when theatres nationally were coming down rather than going up.

Key to its success, as Evershed-Martin conceived it, was that Chichester’s should be a distinct theatre with a distinct season:

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad“Obviously a large theatre such as I was contemplating could not be sustained throughout the year; but it seemed good economics to run it as a festival during the summer, skim the cream during that time, and close down in the winter to save a good proportion of the overheads.”

Back in 1959, Evershed-Martin’s point was that it had to leave people wanting more:

“The festival must be a special occasion which people look forward to, watching for the opening of the booking period and making their plans accordingly. When the theatre is always there it is easy to say ‘I must go there sometime,’ and procrastination produces ultimate inertia.”

Evershed-Martin spoke of his “dream of making theatre with the immediacy and passion of the Greeks – where the community would come to the theatre to debate important issues, to celebrate on holidays, to have serious fun.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAgain, it was an approach which underlined the importance of the concept of a Festival. And it was with these thoughts in mind that Evershed-Martin went to meet Guthrie in person. Evershed-Martin recalls that Guthrie was helpful but cautioned him against the enormous difficulties which lay ahead. Nevertheless, it was all the encouragement Evershed-Martin needed…

Evershed-Martin confided his ambition to create a new theatre in Chichester to the Chichester Town Clerk of the day, one Eric Banks. Evershed-Martin soon also confided in Lord Bessborough at his nearby Stansted home and so gained a crucial ally in the years ahead. On July 1 1959 Evershed-Martin, recently a councillor himself, put the idea of a theatre to Chichester City Council sitting in camera. They agreed in principle a 99-year lease at a peppercorn rent for the Oaklands Park site Evershed-Martin had in mind.

Evershed-Martin then brought in the architects Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya. Their agreement triggered thoughts of launching an appeal – but a very particular type of appeal. And therein lay its success.

Evershed-Martin wanted individual-giving, a kind of giving which would give the individual a sense of ownership, so making the theatre truly a community theatre. Powell and Moya’s plans, when they unveiled them, were a major step forward. “I found the plans very exciting as we pored over them,” Evershed-Martin later wrote, “a superb example of modern architecture that would stand the test of time.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdMeanwhile, fund-raising was gathering pace. Before long, Evershed-Martin had pulled off the most remarkable coup, securing Laurence Olivier to come to Chichester to lead the city’s fledgling theatre towards its bright new future. It was the stuff of dreams - and perhaps that’s one of the aspects of its past most difficult to capture now as the CFT celebrates 60 years and looks back on its roots.

But take a look at the Laurence Olivier archive at the British Library, and you get the distinct impression of a Chichester hardly daring to believe its good fortune.

Olivier, king among actors, was at the peak of his powers, a man in huge demand. Yet here he was in Chichester, at a theatre barely born.

The Laurence Olivier archive, bought for the nation in the millennium year, underlines just how remarkable the moment was. Across several hundred letters over almost five years, the Chichester section of the archive captures the daring of the moment; the thrill of a bold new chapter in British theatre. Chichester believed it held the ace. And that ace was Olivier himself.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdAs the theatre contemplated its third season, Evershed-Martin wrote to Olivier: “I doubt whether you can possibly realise how much your actual presence during the last two seasons in Chichester has created a feeling of trust and confidence in everybody.”

For the latest breaking news where you live in Sussex, follow us on Twitter @Sussex_World and like us on Facebook @SussexWorldUK

Have you read: Hastings panto announced

Have you read: Exploring the great joys of the South Downs WayHave you read: Titanic The Musical heads to Southampton

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHave you read: So many reasons to celebrate as Chichester's Pallant House Gallery marks 40 yearsHave you read: Search begins for 2022 Sussex Young Musician

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide Ad